Melayu popular music in Indonesia, 1968–1975 (Andrew N. Weintraub)

Here, the musical development and socio-cultural meanings of pop Melayu (or Melayu pop)are discussed, a popular music genre created in Jakarta during the late-1960s that achieved commercial success in Indonesia during the 1970s. Pop Melayu blended Western-oriented pop and localized Melayu (also called Malay) music into a hybrid commercial form. Pop and Melayu had different symbolic associations with music, generation, social class, and ethnicity in Indonesia. Pop was marketed mainly to younger listeners who viewed it as ‘cool’ (gengsi) and progressive (maju). For this younger audience, ‘pop’ looked to the future. Conversely Melayu music had the connotation of ethnicity, tradition, and authenticity. Melayu music, as performed by Malay orchestras called orkes Melayu had a large audience base, but was not trendy. Under these conditions, what was the impetus for recording companies, producers, and musicians to create pop Melayu? What did the music mean to musicians, producers, and listeners within the context of culture and politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s? What were the implications of blending pop and Melayu for the future of Indonesian popular music?

During the politically and economically transformative period of the 1960s, pop Melayu grounded the present in the past. As Indonesia moved toward a system of Western-style capitalism, sustained industrialization and intensified commodification of culture, pop Melayu sonically transcoded images and memories of the past, albeit an imagined past, for Indonesian listeners. I borrow this concept of ‘transcoding’ from Ryan and Kellner’s analysis of film and social life: ‘Films transcode the discourses (the forms, figures, and representations) of social life into cinematic narratives. Rather than reflect a reality external to the film medium, films execute a transfer from one discursive field to another’ (Ryan and Kellner 1988:12). I will suggest that pop Melayu in the 1960s and 1970s mediated the contradictions and ambivalence of everyday life during a period of rapid social and cultural change. Musicians, recording companies, and producers were cultural mediators in this process.

In this chapter, I will describe the social and cultural conditions that made it possible to articulate ‘pop’ and ‘Melayu’ as a new genre. As a crossover genre, pop Melayu was a commercial effort to expand the market for popular music by bringing together or unifying diverse audiences. By 1975, a large number of prominent bands and singers had recorded pop Melayu albums.

Bands that recorded pop Melayu albums:

Celebrated singers, Tetty Kadi, Emilia Contessa, Mus Mulyadi and Eddy Silitonga also recorded pop Melayu albums during the 1970s.

I situate pop Melayu within the social and cultural conditions of modernity in Indonesia in four thematic ways. First, its creative flowering coincided with the first decade of the New Order capitalist state in Indonesia. New private recording companies and private radio stations stimulated the development of new forms of music, new ways of advertising music, and an increase in sales of recordings. Second, as a ‘text’ about modernity, pop Melayu marked a transition between something old and something new. Change was articulated through sound, visual representation, and the discourse about pop Melayu in popular print media. Third, it was a form of modernity marked by ethnicity and specific to Indonesia. This “ethno-modernity” presented more than two alternatives: either the American-infused pop music of the future or the Malay-inspired music of the past. Fourth, it was music produced for a young generation and it helped set the course for the future of popular music. One article referred to pop Melayu musicians as the ‘generation of 1966’ (‘angkatan ‘66’); ‘Regrouping musikus Angkatan ‘66’ (1968:5).

Pop Melayu refers to a commercial genre of popular music and not simply any kind of popular music in the Malay (or Indonesian) language. My focus will be on the commercial genre of pop Melayu, and not other forms of Melayu popular music or popular music in the Indonesian language (bahasa Indonesia). Nor will this chapter address songs composed previous to the era of pop Melayu which might be considered precursors or progenitors of pop Melayu. Data are based on interviews with musicians, analysis of music and lyrics, depictions on record covers, and critical readings of popular print media from the period. I am grateful to Hank den Toom, Jr. for providing me with recordings from the period, and Ross Laird for recording data. I would also like to thank Shalini Ayyagari, Bart Barendregt, Henk Maier, Tony Day, and Philip Yampolsky for helpful comments during the writing of this essay. Particular emphasis is given to the work of Zakaria, an influential musician, composer, and arranger. The scope covered in this chapter encompasses the formation of pop Melayu around 1968 and it ends in 1975 when two things happened: (1) pop Melayu was established as a mainstream genre in the music industry; and (2) Rhoma Irama began taking contemporary Melayu music in a different direction, namely dangdut, which blended rock with Melayu. My interest here lies in the development and meaning of pop Melayu in its formative period.

Melayu

Central to my discussion of music in mid-1960s Jakarta is the notion of ‘Melayu’or Malayness. Melayu is a word of great slippage, and therein lies its productive force: it allows people to authorize all sorts of meanings (Andaya 2001). Defined in the colonial period as ‘stock,’ race, and ethnicity on the basis of biological appearances, Melayu implies a core set of ideas, values, beliefs, tastes, behaviours, and experiences that people share across geographical areas and history (Barnard and Maier 2004). The concept and naming of Melayu as culture and identity existed before colonialism but not as a way of organizing people according to physical markers of race and ethnicity. Some differentiation is necessary, and perhaps the terms ethnicity and race can be usefully applied. For example, Malays as an ethnic group (suku Melayu) resided around the Melaka Straits and Riau whereas Malays as a racialized group (rumpun Melayu) populate the modern nation-states of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, and (southern) Thailand in Southeast Asia. Yampolsky (1996:1) refers to the ethnic group as the ‘primary’ area of Melayu culture, and to, what I would call, the racialized group as the ‘secondary’ area of Melayu culture. For further on the construction of Melayu as a social category see Andaya 2001; Shamsul 2001; Reid 2004; Kahn 2006 and Milner 2008. However, Melayu never represented one uniform discourse, practice, or experience exclusive to all members of that group (Barnard and Maier 2004:ix). As a discursive category, Melayu has always been constructed, imagined, fluid, and hybrid. Melayu was an arena of constant reinvention. Notions of Melayu culture, language, and identity have always operated situationally and contextually (Andaya 2001).

What frames Malayness as a discursive category in popular music of the 1960s and 1970s in Indonesia? In contrast to the mistaken colonial idea of Malayness as cultural homogeneity and origins, I invoke Homi Bhabha’s notion of ‘ambivalence’ to understand the simultaneous attraction and aversion to Western colonial cultural forms in post-colonial Indonesia of the 1960s (Bhabha 1994). I aim to show how Malayness in popular music discourse of 1960s Indonesia represented: (1) the blending of Malay indigeneity and tradition (discursively constructed as ‘Melayu asli,’ or the ‘original’ or ‘authentic Melayu’) with Western forms, ideas, and practices; and (2) a ‘third space,’ where signs of the past could be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized, and read anew (Bhabha 1994:36; Rutherford 1990). In the politically transformative period of 1960s Indonesia, pop Melayu music formed links with discourses of indigeneity and tradition while simultaneously articulating with commercialization and modernity.

Melayu as a category of musical composition and performance did not represent a return to tradition in the face of modernity. Stylistic experimentation and compositional variety had long characterized Melayu popular music. The musical genres bangsawan, orkes harmonium, and orkes gambus of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries played mixed repertoires of Indian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, and Malay music. Orkes Melayu (Malay orchestras), which I will discuss further, continued this trend. Bangsawan (also called opera and stambul) troupes travelled from Malaya (Malaysia) to Java in the 1890s (Tan 1993:73; see also Cohen 2006; Takonai 1997 and 1998). Named after the harmonium, a small reed organ from Europe via India, orkes harmonium (or O.H.) included harmonium, violin, trumpet, gendang (small two-headed drum), rebana (frame drum), and sometimes tambourine. Radio logs indicate that orkes harmonium played a mixed repertoire of Malay, Arabic, Indian, and European music (Weintraub 2010:39-40). Gambus orchestras featured the gambus (long-necked plucked fretless lute) or ‘ud (pearshaped lute) and were accompanied by small double-headed drums (Ar. marwas, pl. marawis). Immigrants from the Hadhramaut region (Yemen) presumably brought the gambus and marwas with them to Indonesia (Capwell 1995:82–3). Even the term ‘orkes Melayu’ suggests mixing and contradiction: ‘orkes’ (from the Dutch ‘orkest’ or the English ‘orchestra,’ which denoted modernity) and ‘Melayu’ (signifying a cultural past). Melayu popular music was a ‘hybrid language’ (bahasa kacukan), the kind that always breaks the rules rather than follows ‘correct’ and standardized usage (Barnard and Maier 2004). Further, Melayu was a term of perspective: for example, ‘orkes Melayu’ had different musical properties and symbolic associations in Medan, Surabaya, and Jakarta during 1950 to 1965 (Weintraub 2010).

In the following section, I will trace the historical development of pop Melayu based on my interpretation of musical recordings, popular print media, and interviews with musicians and producers who were active during the period. I begin with the period of Sukarno’s Old Order (1949– 1965) because it informs an understanding of ‘pop’ for the purposes of this essay. I will focus on the formative period of pop Melayu recording, which occurred during 1968 to 1975 in Indonesia’s capital of Jakarta, the center for the production and consumption of pop Melayu.

The (Late) Old Order

The politically transformative decade of 1960s Indonesia is often characterized in terms of the fiercely anti-colonial and socialist-leaning Sukarno regime and the capitalistic and neoliberal economic policies of the Suharto regime. The transition from Sukarno’s Old Order (Orde Lama) to Suharto’s New Order (Orde Baru) took place mid-decade, after the military coup and subsequent killing of 500,000 to a million people beginning on October 1, 1965. Knowledge about cultural history of the period has been buried, particularly in Indonesia, due to the Suharto government’s effort to erase the PKI and the Left from the historical record. Recent scholarship has begun to investigate the cultural history of Indonesia 1950–65, particularly in terms of literature (Foulcher 1986; Day and Liem 2010; Lindsay and Liem 2012). However, studies of popular culture, especially popular music, remain unexplored (Lindsay 2012:18).

During the late 1950s, the anti-imperialist regime of Indonesia’s first president Sukarno denounced the allegedly harmful influence of American and European commercial culture (Frederick 1982; Hatch 1985; Sen and Hill 2000). The Committee for Action to Boycott Imperialist Films from the USA (PAPFIAS) boycotted American films in 1964 (Biran 2001:226). Sukarno viewed American and British music as symbolic and material markers of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. During a speech in 1959, Sukarno criticized the grating sound of American popular music, using the non-literal sounds ngak-ngik-ngok to characterize its noisy clatter (Setiyono 2001). As a result, popular music bands with Englishsounding names were compelled to switch to Indonesian ones to disarticulate the influence of American music. In a speech in 1965, Sukarno declared that ‘Beatle-ism’ was a mental disease and that he had ordered the police to cut the hair off anyone found listening to the Beatles (Farram 2007). Sukarno even imprisoned members of the American and British-influenced pop music band Koes Bersaudara (Koes Brothers) for 100 days in 1965 (Piper and Jabo 1987:11). As interesting and important as this case may be, I will not discuss Koes Bersaudara in this essay because I feel that their case has been covered amply in the literature on Indonesian popular music of the 1960s. Largely due to the banning and jailing of Koes Bersaudara, historians of the period have focused on Sukarno’s hostility to Western popular music (Lockard 1998; Sen and Hill 2000; Farram 2007).

Emphasizing the Old Order’s hostility to Western pop tends to obscure the diverse activities of musicians, producers, recording companies, and fans of popular music. Indeed, Sukarno attempted to ban Western popular music recordings from entering Indonesia in the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, despite Sukarno’s aversion to the sound of Western popular music, it still managed to cross geo-political borders. Although Western popular music was limited by government regulation on the national radio network RRI (Lindsay 1997:111), hundreds of illegal studentrun radio stations in Jakarta broadcast prohibited recordings of American popular music (Sen 2003:578). Recording companies continued to produce American- and British-sounding popular music, following trends established in the early 1950s. In addition, songs inspired by popular music of India, the Middle East, and Latin America energized the repertoire of the many orkes Melayu groups in urban Indonesia (Frederick 1982; Takonai 1997 and 1998; Weintraub 2010). Sukarno himself encouraged producers, composers, and musicians to mix regional songs with Western musical elements (Piper and Jabo 1987:10). Despite claims that the early 1960s was one of the most repressive periods in Indonesian music history, complete with national government censure of recording, radio, and public performances, the music of this period was productive in shaping ideas about modernity along the axes of social class, gender and ethnicity.

Orkes Melayu and pop Indonesia constituted distinct genre categories in terms of song lyrics/themes, language(s) used, instrumentation, performance practices and occasions, and audience. In the following section, I will elaborate on these genre categories and describe how pop Melayu combined elements of orkes Melayu and pop Indonesia.

Orkes Melayu

In 1960s Jakarta, orkes Melayu (O.M.) was an important genre term, but it actually describes several different kinds of ensembles, performance practices, and publics. At a very basic level, orkes Melayu was an ensemble of musical instruments (an ‘orkes’ or ‘orchestra’) used to accompany Malay-language songs. Songs were sung in a vocal style characterized by distinct kinds of ornaments (called gamak or cengkok) conventionally associated by musicians with the music of the Melayu ethnic group. Song forms included pantun verse structures as well as modern sectional forms (e.g., AABA). Pantun are made up of two couplets, generally structured into four lines with the rhyme scheme ABAB. The songs may have come from the geographic region considered the homeland of Melayu culture (in the southern Malay peninsula, Malacca, eastern Sumatra, and Riau), but they could also have been newly composed in a Melayu style in other parts of Indonesia including Jakarta. Either way, the repertoire, vocal style, and certain instruments in the ensemble signified a connection to Melayu ethnic identity or Malayness.

The instrumentation was not set. Recordings of orkes Melayu and photographs from the early 1960s reveal ensembles of Western instruments and two indigenous instruments, namely a small double-headed drum shaped like a ‘capsule’ (gendang kapsul) and bamboo flute (suling or seruling). The Western instruments could include accordion, violin, piano, vibraphone, acoustic guitar, string bass, woodwinds (flute, clarinet), brass (saxophone, trumpet), and percussion (maracas, in addition to the gendang kapsul). The historical and symbolic associations of the violin and accordion with Melayu music had been established earlier (Yampolsky 1996). Orkes Melayu bands could be heard on national radio programs, recordings, and in films. Although orkes Melayu has often been referred to as kampungan (regressive, backward, rural), it is hard to imagine these ensembles as such due to their centrality in mass media. See ‘Elvy Sukaesih’ (1972:18); ‘Peta Bumi Musik’ (1973:17); ‘Panen Dangdut’ 1975:48. A kampung refers to a neighbourhood that can be located in a village, town, or city. Kampungan connotes inferiority, lack of formal education, and a low position in a hierarchical ordering of social classes (Weintraub 2010; see also the next chapter by Emma Baulch).

Another kind of orkes Melayu was a pick-up group that performed in a variety of settings. Orkes Melayu was discursively coded as music of ‘ordinary people’ or ‘masses’ (rakyat). They were denigrated by elite youths as ‘kampungan’, country bumpkins, because they played an older kind of music. Orkes Melayu musicians and audiences themselves never thought of themselves as ‘kampungan,’ a term that expressed disdain. Orkes Melayu musicians in Jakarta viewed Melayu music with a certain amount of nostalgia, as expressed in the following quote by Zakaria in 1975:

Looking back for a moment, the birth of Melayu songs is like a step-child without a father. They were born on the side of the road, in ramshackle huts, next to railroad tracks, in food stalls, or in places where villagers hold celebrations, and even in lower class prostitution quarters. They danced to their heart’s content as they joked around to their dying day. They enjoyed these kinds of songs because they are easy to remember, the language is simple, and they are nice to listen to. Besides these psychological factors, the song texts give voice to suffering, love, sex, etc. Those songs, which are indeed sentimental at heart, are very appropriate to the emotional states of their listeners. See Zakaria (1975), ‘Sensasi Pop Melayu Ditahun 1975: “Begadang” yang jadi bintang’, Sonata 53, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

A comparison with pop music is instructive. Orkes Melayu bands had fewer resources than pop music bands. For example, they performed with only one microphone for the singer and one or two speakers for amplification. They were seen by elites as lagging behind pop music because they did not play electric instruments (guitar, bass, organ).

Their music was a hodgepodge and was viewed in a negative light by elites as impure or hybrid. Since the early 1950s, Indonesian composers had been copying Indian melodies from film songs and composing new lyrics in Indonesian. They played dance music with a wide range of Zakaria, pers. com., 2005). On the one hand, the repertoire for Orkes Melayu was old and conservative. On the other hand, the repertoire was vast and cosmopolitan and included Indian, Middle Eastern, Latin, and European songs. It did not look to the past or the present; it looked in many directions at once.

Pop Indonesia

The nascent genre of pop Indonesia referred to music whose repertoire, song forms, arrangements, and instrumentation were rooted in American and British popular music. Also called band or band remaja (youth band), pop Indonesia was geared primarily to an emerging middle- and upperclass youth culture (‘the middle classes and up’). Pop Indonesia bands often played indoors in buildings (gedung), and earned the epithet gedongan (from gedungan) which implied class distinction and ‘progressive’ attitudes. Composer and musician Guruh Soekarnoputra, the son of Indonesia’s first president Sukarno, stated that the term gedongan and kampungan stemmed from identification with class distinction:

Pop Music in the past came to our country via ‘privileged youngsters’ whose parents had bought records from outside the country. They played these records at home and their friends heard them. Then they bought ‘band’ instruments and played them at their parties. Eventually the music got on the radio stations run by those youngsters. At that point youngsters outside [privileged residential districts] of Menteng and Kebayoran heard them. They began to think that this music was cool, and if someone was not familiar with that music, they would be considered a ‘country bumpkin’ (Soekarnoputra 1977:48). ‘Musik pop dahulunya masuk ke negeri kita lewat ‘anak-anak gedongan’ yang orangtuanya bisa membeli piringan hitam di luar negeri. Lalu diputar di rumah, dan kawan-kawannya mendengarkan. Kemudian mereka beli alat-alat band, bikin pesta dan main di sana. Akhirnya masuk ke pemancar-pemancar radio yang dibikin anak-anak muda. Mulailah anak-anak luar Menteng dan Kebayoran mengenalnya. Lantas timbul anggapan bahwa inilah musik keren, dan kalau tidak kenal sama musik demikian, bakal tetap jadi ‘orang kampung’.

Pop Indonesia was modeled on Euro-American mainstream popular music including pop, rock, and jazz. Pop Indonesia songs were accompanied almost exclusively by Western instruments (primarily guitar, bass, drums, and keyboard). Bands had a microphone for each person and multiple speakers. The language of pop Indonesia songs was Indonesian and English. It often incorporated vocal harmonies, in contrast to orkes Melayu, which generally consisted of a solo vocal part accompanied by instruments. Themes centred on romantic love. Musicians were often trained to read scores. They had financial backing that allowed them to purchase fine-quality instruments (Dunia Ellya Khadam 1972:36). Private radio played a large role in disseminating new forms of popular music during the New Order. During the Old Order, the national radio network RRI, as part of the Ministry of Information, had sole authority for broadcasting (Lindsay 1997:111). Amateur HAM radio operators existed and even had their own association; this type of operation was called amatir radio (which was different from radio amatir).

Private radio stations (radio amatir), suppressed during the Old Order, came back as part of the student movement of 1966 (Lindsay 1997:111). During the late 1960s, especially in Jakarta and Bandung, competing radio stations battled for airwave frequencies (Lindsay 1997:111). Private commercial radio stations flourished in the early New Order period (early 1970s), and they set themselves apart, respectively, by playing different kinds of music from each other.

In the late 1960s, production of popular music recordings increased. The Soeharto regime encouraged capital expansion in all sectors of the economy. Recording companies looked for ways to expand the market for products. Distinct markets existed for pop and Melayu in terms of recordings, concerts, and audiences, and both were successful. New fusion genres formed out of old ones. In the following section I will describe the efforts of the musician, composer, and bandleader Zakaria (1936–2010) who in the early 1960s began composing songs that blended pop with Melayu music.

‘Becoming Melayu’: The Work of Zakaria

Zakaria was born in 1936 in the area of Paseban in East Jakarta. He sang Melayu songs as a child growing up and cited the songs of the Malaysian singer and film star P. Ramlee as an important influence (pers. comm, 2005). Zakaria was self-taught as a musician (guitar) and was a talented singer. In 1956, he began singing with several orkes Melayu bands including Orkes Sri Murni (led by M. Masyhur) and Orkes Cobra (led by Achmad B.). He joined Said Effendi’s Orkes Melayu Irama Agung as a percussionist in 1957, and began composing shortly thereafter.

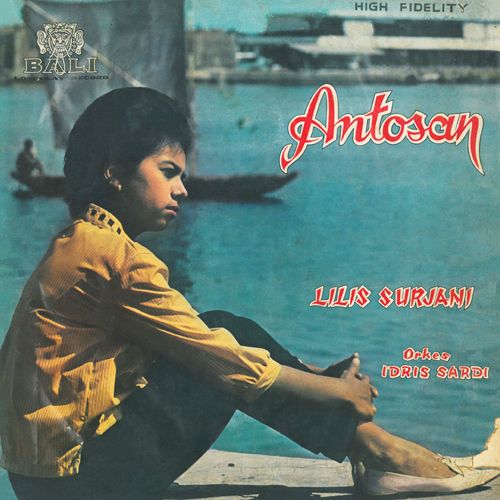

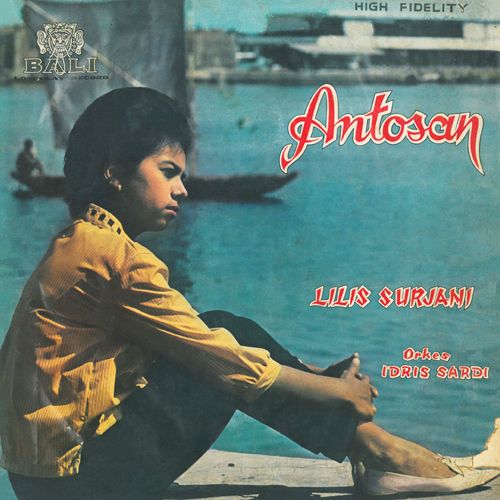

In 1962, he formed a group called Pancaran Muda (‘The Image of Youth,’ also called Orkes Melayu Pancaran Muda and Orkes Pancaran Muda). The band had a modern sound. With support from Jakarta’s popular entertainer Bing Slamet, Zakaria learned how to arrange music for an orchestra. He also worked on songs and new arrangements with pop and jazz pianist Syafei Glimboh, as well as violinist Idris Sardi. Zakaria’s songs com- bined elements of both genres. For example, in the song Luciana, the refrain (‘Luciana’) was composed in a pop style whereas the verse was Melayu (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). From the album Antosan featuring Lilis Surjani accompanied by Orkes Idris Sardi, Bali Record RLL-002, released in 1965–66.

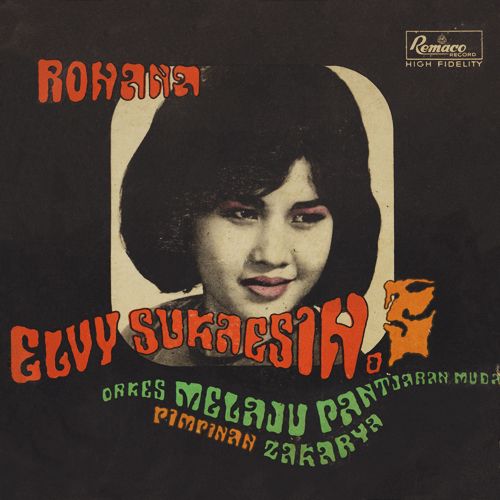

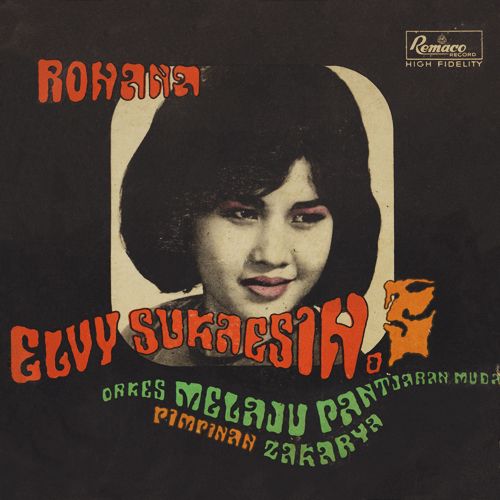

In 1964, Zakaria produced the first commercially released songs by Elvy Sukaesih, a young 13-year-old singer who would later earn the moniker 'the queen of dangdut' (ratu dangdut). Elvy Sukaesih could sing both Melayu music and pop music and the songs on her first album were accompanied by a group made up of orkes Melayu musicians and pop (band) musicians. The session took place at the Remaco recording studio on December 19, 1964 and the record was released in January, 1965. The session included the following songs:

Zakaria’s Pancaran Muda did not emphasize the Indian-derived sound of orkes Melayu, which was discouraged in 1964 as the central government was trying to divert attention from Indian culture and refocus it on Indonesia. The Sukarno government, which had vigorously encouraged Indian film imports during the late 1950s and early 1960s, changed course by ceasing to allow imports during 1964–1966. As Indonesia became more isolated politically, songs with an Indian flavor (berbau India) were discouraged from being played on the radio (Barakuan 1964: 21; 'Orkes Melayu Chandralela’ 1964:21; ‘Dangdut, sebuah flashback’1983:15). The Indianderived songs of orkes Melayu, some of them direct copies from popular Indian films, were the targets of these efforts.

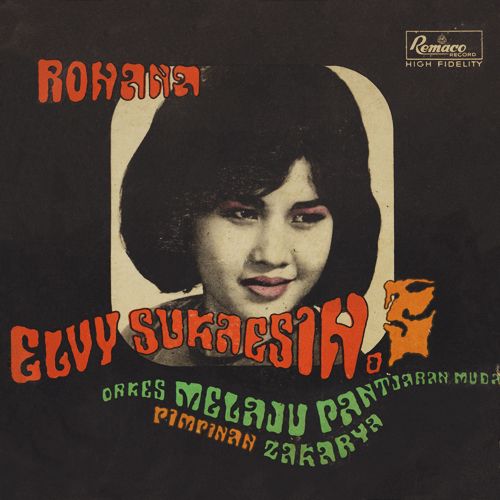

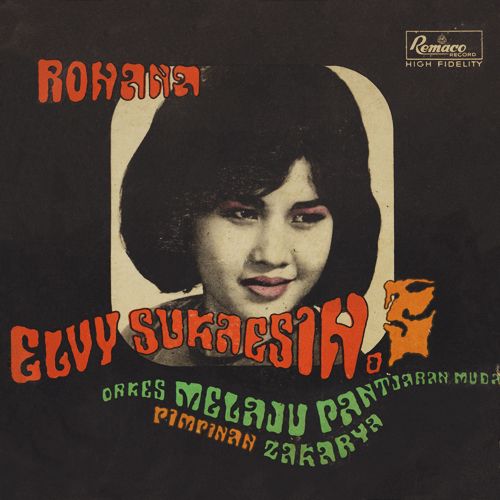

Zakaria mixed what he describes as ‘Melayu-India’ songs with Indonesian ones. In a description of his music taken from the album cover of Rohana released in 1967–68, Zakaria is quoted as follows: Liner notes written by Jul Chaidir on the back cover of the album Rohana featuring Elvy Sukaesih accompanied by Orkes Melaju Pantjaran Muda, directed by Zakaria (Remaco RL-050), c. 1967–68.

The song style that I present on my recordings is a mixture between music of Melayu-India and [pop] Indonesia itself. Since I do not copy a particular foreign song and then give it an Indonesian text, the songs will not sound like songs whose melodies and rhythms simply copy Indian songs. Tjorak lagu2 jang saja hidangkan dalam rekaman2 saja, ialah tjampuran antara lagu Melaju-India dan Indonesia sendiri. Djadi saja tidak menjeplak sesuatu lagu luar untuk kemudian diberikan teks Indonesia, oleh karena itu dalam lagu2 ini tidak akan terdengar lagu2 jang nada dan iramanja menjeplak lagu2 India thok.

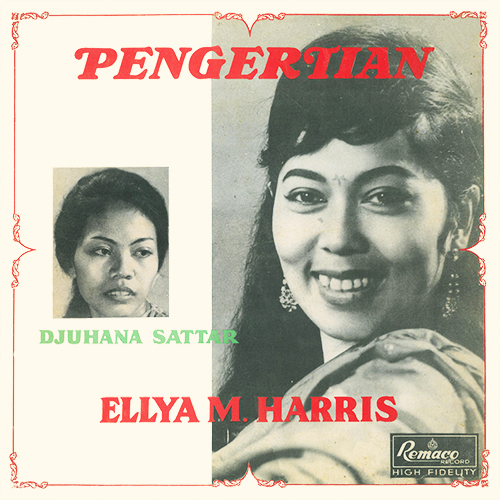

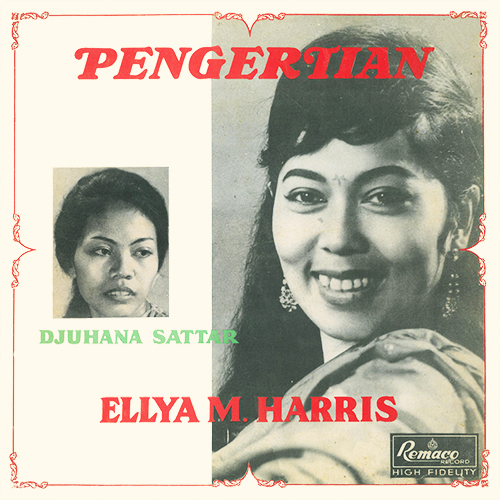

There was a vacuum in popular music recording after the military coup and subsequent regime change from Sukarno’s ‘Old Order’ to Suharto’s ‘New Order’ in 1966–1967. From 1961 to 1963, Irama produced as many as 30,000 discs per month, but by the end of 1966 only pressed about 1000–2000 per month (and only sold about 500 per month) (MYK 1967). A similar gap is evident in Lokananta’s production of hiburan music (Yampolsky 1987:119–20). Deregulation of film imports, which began on 3 October 1966 (Said 1991:78), enabled greater access to foreign film music. Zakaria promoted singer Lilis Suryani as a competitor to singer Ellya Khadam, the top orkes Melayu singer of the era known for her Indianinspired songs Termenung (Daydreaming, c. 1960), Boneka dari India (A doll from India, 1962–63), and Kau pergi tanpa pesan (You left without a word, 1967); the latter was considered a ‘comeback’ for Melayu music à la India. From the album Pengertian featuring singer Ellya M. Harris accompanied by Orkes Melayu Chandralela, directed by Husein Bawafie (Remaco RLL-011), c. 1967.

Previously criticized by Sukarno as a symbol of imperialism and capitalism, American popular music was encouraged under the new president Suharto. Recordings of American-influenced pop Indonesia boomed in the late 1960s.

Zakaria was a savvy promoter of his band Pancaran Muda. Descriptions of Zakaria in popular print media depict him as a musical soldier for the nation. For example, ‘he had a face that looked like a soldier’; Tokoh Wadjar, 19 December 1965, as found in the private collection of Zakaria. another journalist referred to him as a ‘general’ of the band Pancaran Muda (bertindak sebagai panglima perangnya). His work was characterized as ‘revolutionary art’ (seni untuk revolusi) because it supported ‘the motherland that must be defended to the death’ (ibu pertiwi yang harus dipertahankan mati-matian). Mingguan Wadjar, 19 December 1965, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

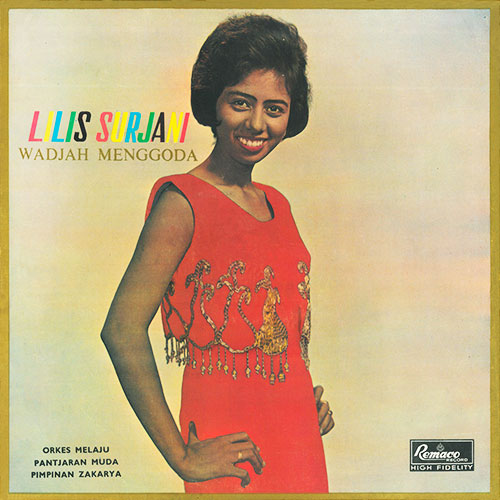

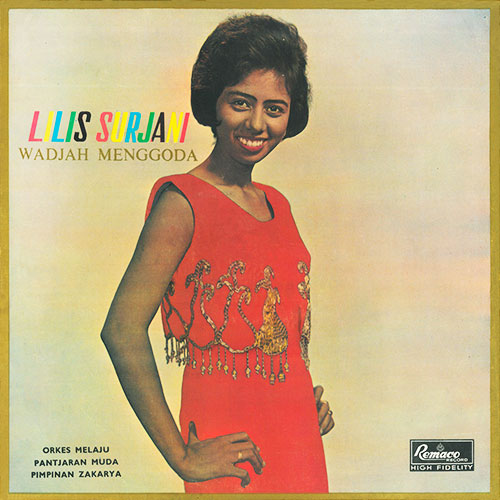

In the late 1960s, Melayu-inflected songs accompanied by pop bands ascended in popularity. Successful songs in this vein included Boleh-boleh (It’s allowed) sung by Titik Sandhora and accompanied by Zaenal Combo (1968); Wajah menggoda (Seductive face) sung by Lilis Suryani (Remaco RLL-018, 1968),

and Tiada tjerita gembira (Not a happy tale) sung by Muchsin Alatas (Remaco RL-050, 1968).

After seeing positive sales figures from these and other songs, the Remaco recording company hired Zakaria as a producer, composer, arranger, and talent scout. Zakaria was instructed to create Melayu songs for a stable of pop singers:

Mr. Yanwar, the director of my section, told me that every singer who recorded at Remaco had to have a Melayu-type song on each record. It was a good opportunity for me [a composer of Melayu songs] that fans and pop singers liked Melayu songs. Subsequently, pop Indonesia bands like Bimbo, Koes Plus, Eka Jaya Combo, and 4 Nada recorded pop Melayu songs. (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005)

Zakaria taught pop singers Mus Mulyadi, Lilis Suryani, Wiwiek Abidin, and Titiek Puspa, among others, how to sing vocal ornaments typical of Melayu music (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). They were trained to sing in a more strident timbre than used in pop. Zakaria taught them to sing without too much vibrato, a hallmark of pop music. (Rh)Oma Irama, who had achieved success as a pop singer before becoming a star of contemporary Melayu music (dangdut), honed the Melayu vocal style by working with Orkes Melayu Chandralela bandleader Husein Bawafie who remarked: ‘He was often told not to sing with too much vibrato. Because dangdut is different from pop.’ (‘Ia sering diberitahu agar tidak terlalu banyak menggunakan vibra (getaran). Pasalnya, bernyanyi lagu dangdut berbeda dengan pop’ (Tamala 2000, no page numbers available). According to the composer, singer, and journalist Yessy Wenas, singers of Melayu songs had to be able to produce rich tonal variations, triplets, portamenti, punchy (staccato) tones, partial wailing, and shrill sounds. (Yessy Wenas, pers. comm., 2012). Penyanyi lagu Melayu harus punya teknik intonasi yang kaya variasi, not triol satu ketuk tiga nada, nada mengayun, menyentak, setengah meratap, melengking. He noted:

The singer Wiwiek Abidin felt stiff and encountered many problems when she began learning the ornaments of Melayu songs. But after a while she figured out how to sing in the style of Melayu songs in her own distinct way. Wiwiek commented that singing Melayu songs is easy to hear but difficult to follow because there are so many ornaments and there are almost no breaks [in vocal phrases]. She said that there are no definite rules, and only the composer of the song knows [the parameters of the composition]. (Lagu2 ‘dang dut’ mulai di senangi banyak orang, c. 1974). Penyanyi Wiwiek Abidin … merasa canggung dan menemui banyak kesulitan ketika baru mulai mengenal lekukan2 (intonasi) lagu2 melayu. Tapi lama kelamaan dia temukan juga gaya2 lagu melayu yang tersendiri ciri kasnya itu… Wiwiek memberikan komentar bahwa menyanyi lagu melayu adalah gampang di dengar tapi susah di ikuti, karena lekuk2an lagu melayu banyak sekali belok2nya dimana batas lekukan2 itu hampir tidak ada, katakanlah tidak ada patokan yang pasti, hanya pengarang lagunya saja yang tau’. See Wenas. J. (date unavailable, c. 1974), ‘Lagu2 “dang dut” mulai di senangi banyak orang’, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

Yessy Wenas’s commentary noted that Suryani had figured out how to sing in a Melayu style (albeit in her own way). Despite not knowing the parameters of the style, she was able to recreate a style of singing that was convincingly Melayu-sounding. The composer Zakaria had his own definition that stressed the compromise or in-betweenness of pop Melayu. It was not ‘either/or’ but ‘both/and.”’ Zakaria defined pop Melayu simply as ‘When a pop singer sings a Melayu song in a pop vocal style accompanied by a pop music band’ (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). They may have inserted an ornament here and there, but the vocal style emphasized pop rather than Melayu.

Musical Style of Pop Melayu

In the following section I will examine two songs that merged pop and Melayu, focusing on texts and musical characteristics.

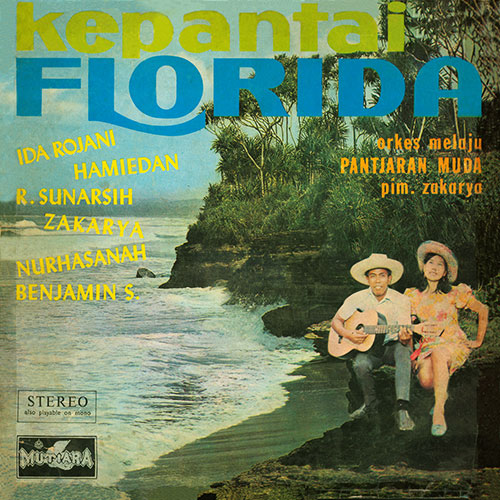

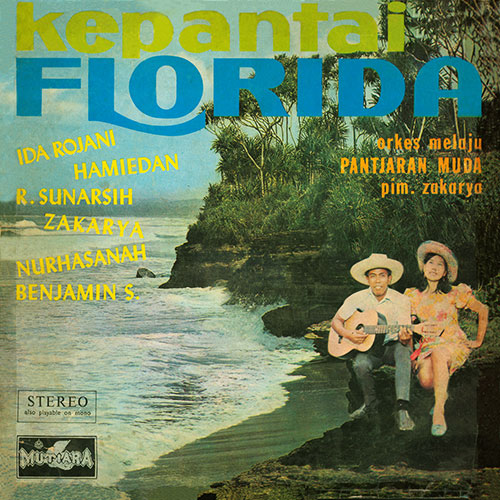

Djangan duduk di depan pintu (Don’t sit in front of the door), c. 1970, exemplifies the Melayu modernity of pop Melayu. The song is from the album entitled Kepantai Florida ([Let’s go] to the beach in Florida, Mutiara Records MLL 025). The cover of the album shows a photograph of Zakaria and female singer

Ida Rojani dressed in casual beach attire sitting on a rock (Fig. 5.2). The photograph is pasted against a background that looks more like the coast of Java than the southern gulf of the United States. ‘Florida’ was not a place that ordinary people would actually go for a vacation, but it was a sign of escape and play. In Djangan duduk di depan pintu sonic markers of Melayu music include the percussion parts played on a gendang kapsul (a small double-headed drum shaped like a ‘capsule’) and tambourine. Other key markers of Melayu music are accordion and violin, which appear in other examples (see below). Markers of modern music include piano, vibraphone, and electric instruments (bass).

In her pop music recordings, the singer Lilis Suryani often used a smooth and syrupy vocal quality that was similar to her American counterparts. In this example, however, Lilis Suryani sings with a strident tone. Unlike Melayu singers, who inserted characteristic ornaments toward the ends of phrases, this vocal style is largely unornamented.

Despite the American influences in instrumentation and vocal timbre, the two singers engage in a dialogue common in pantun-structured Melayu music. They express themselves in the style of the Indonesian language spoken in Jakarta.

Example 1: Djangan duduk di depan pintu

Album Kepantai Florida; Mutiara Records MLL 025 (side 1: ML 12247), c. 1970

Composed by Zakaria

Sung by Zakaria and

Ida Rojani

F=father

D=daughter

Album cover Kepantai Florida ([‘Let’s go) to the beach in Florida’), Mutiara Records MLL 025, c. 1970, featuring Orkes Melayu Pancaran Muda, directed by Zakaria.

Djangan duduk di depan pintu is a saying that literally means ‘don’t sit in front of the door’ (because you will block the path of those going in and out). Symbolically, ‘sitting in front of the door’ stands for being too aggressive. ‘Don’t sit in front of the door’ is a warning for young girls: ‘you’ll never get married if you’re too aggressive.’

Yet, the young daughter in this example resists her father’s advice, and insists on ‘sitting in front of the door.’ She asserts her will to finish school so that she can become a doctor and take care of everyone in the village. This exchange between a father and daughter translates intergenerational conflict and the changing role of women into song. This kind of conflict, and the striving of women for equality, goes back to the colonial period, but had a different intensity in the context of the late 1960s and early 1970s. On the one hand, women were cast as wives and mothers as part of the gendered ideology of the Old Order. On the other hand, melayu popular music in indonesia, 1968–1975 181 with increasing industrialization during the late 1960s, women became increas ingly important actors in the workforce (Robinson 2009:90). In this song, the public transformation of gendered identities has become a private family matter, discursively transcoded for a public audience in popular song. The daughter rejects male patriarchy, which circumscribes a woman’s role as housewife and mother. Eventually the father comes around to the daughter’s point of view, signifying acceptance of the woman’s desire. From an old patriarchal saying about sitting in doorways, to a new articulation of women, education, and work, this short upbeat song transcodes the social transformation of gendered and generational identities.

The vocal style of the music contributes to the narrative meaning of this song. The first voice one hears in the song is the father, who sings ‘don’t sit in front of the door.’ His daughter respectfully challenges him in a somewhat malu manner (shy, reticent, reserved). She articulates her refusal in a relaxed manner, somewhat behind the beat, stretching her words over the main beat. The woman’s voice seems to get louder and more strident with each successive verse, as the male voice recedes into the background. By the second verse her words fall clearly on the beat and she is emphasizing her words with more vibrato. By the end of the song, the father sounds like an acquiescent old man, shuffling away in the background. He has shifted his point of view completely, expressing pride in his daughter’s progressive attitude.

In Bila suami kerja (While husband is at work), c. 1975, the accompaniment of gendang, mandolin, and accordion indexes Melayu music of the period. Electric guitar and bass and piano, and especially the unornamented vocal line, articulate a modern sound.

In this fascinating example, a man visits a woman’s home and asks if her husband is there. After learning that her husband has gone to work, he prepares to leave. However, she opens the door and invites him in for a drink. After establishing that she is interested in having an affair, he invites her to a beautiful place to spend a long afternoon together (and maybe an evening).

Example 2: Bila suami kerja

Album Sallama; Indra Records AKL 102 (side 1: TMS 102A), c. 1975

Composed by Zakaria

Sung by Mus Mulyadi and Rifa Hadidjah

m=male

f=female

The freedom and directness of the lyrics are striking. Extramarital affairs were part of everyday life, but were rarely discussed in public. This example translates female agency and desire into song (specifically on the word abang (lit. ‘older brother’ or form of address by wife to husband) which the singer turns into the sexual ah-bang). It is noteworthy that the married woman initiates the affair, while the man is hesitant and coy. In a reversal of conventional male-female roles, in which men speak in public and women are silent, it is the woman who states ‘don’t be afraid to speak your mind!’

The song invites multiple and conflicted readings. In one reading, the song turns male-female relations upside down, and places the modern woman in the position of actor rather than passive receiver. This reading celebrates female sexuality and power. However, we must consider these characters within the moral framework of this tale. In another reading, she is assumed to be the one responsible for the potential breakup of the family. This woman is not only ‘acting,’ but ‘overakting,’ a code word for vulgarity and backwardness. Not only is the woman having an extramarital affair, she is doing it when her husband is at work! In this way, the song articulates with both modern and progressive roles of woman as agential, while also serving as a morality tale about what can happen when women are let loose and ‘not afraid to speak their mind!’ The song thus becomes a sign for struggles over the meaning of changing male-female relations, morality, and sexuality in modern New Order Indonesia. These struggles would continue to be played out in dangdut, a contemporary form of Melayu music that also grew out of orkes Melayu.

The bridging of pop with Melayu as a commercial genre had important implications for the future of pop music in Indonesia. By 1975, most of the top national singers and groups had recorded pop Melayu songs. Pop Melayu invigorated the careers of Jakarta-based pop Indonesia bands Koes Plus, Panbers, Mercy’s, and D’Lloyd. These groups produced their own form of upscale Melayu music characterized as Melayu Mentengan after the expensive residential area Menteng in central Jakarta where youth from privileged families lived (‘Panen Dangdut’ 1975:45).

Why, as stated in a 1975 Tempo magazine article, did the ‘aristocrats’ (priyayi) in the music industry begin ‘lowering themselves’ (turun ke bawah) to sing Melayu music? According to the article, market forces had compelled producers and pop singers to go along with the Melayu trend, sometimes begrudgingly (as in the case of pop singers Titiek Puspa and Mus Mualim). When asked why producers followed the trends of the industry, Ferry Iroth, a producer at the Remaco record company, stated simply, ‘We sell products’ [and Melayu sells] (‘Panen Dangdut’ 1975:3). Popsinger Mus Mualim noted that ‘pop music has an unstable (wandering) quality that always wants to find something new’ (‘Panen Dangdut’ 1975:47). For the pop audience, Melayu music was perceived as something different, trendy, and therefore marketable.

During the early 1970s, pop producers and musicians were competing with dangdut, a form of contemporary Melayu music with roots in orkes Melayu. The popularity of dangdut was a major factor that pushed pop singers and bands to adopt Melayu songs, song forms, and vocal style. Singers who had been trained in orkes Melayu, including Rhoma Irama, A. Rafiq, Elvy Sukaesih, and Mansyur S., were familiar with both Western pop and Melayu music. As dangdut’s popularity soared in the mid-1970s, pop Melayu was gradually pushed aside.

Conclusion

In the mid-1960s, pop Melayu (Melayu pop) combined some of the most progressive (pop) with some of the most conservative (Melayu) music (as well as tinges of Indian film music and Middle Eastern popular music). Melayu stood for music with a strong connection to tradition, a basis in Middle Eastern and Indian music, a link to Malaysia and other Malays, and a community of Muslims. On the other hand, pop Indonesia looked toward the future, was strongly influenced by American pop music, was not considered to have ethnic associations, and was non-religious in nature (although some singers were Christian and some were Muslim). Slipping around this binary and reductionist model of past/future, East/ West, and traditional/modern, pop Melayu composers and musicians wove the past (old) into the present (new).

In contrast to static and essentialized colonial definitions of culture, ‘Melayu’ can more productively be understood using postcolonial theory as hybrid, liminal, and ambivalent. This ‘third space’ sensibility is demonstrated clearly in the genre pop Melayu. I used the term ‘ethno-modernity’ to describe how pop Melayu participated in new ways of seeing oneself as both modern and Malay (‘Melayu’).

In this chapter, I have examined pop Melayu from several different angles. As a form of commercial pop music, pop Melayu capitalized on the popularity of Melayu music to sell records. As a form of Melayu music, it did what Melayu had been doing for a long time: branching out, blending, appropriating, and complicating genre distinctions. Melayu songs composed, arranged, and performed in an American-influenced style were very much part of a Melayu sensibility in music.

Pop Melayu presented more than two alternatives: either the American-infused pop music of the future or the Malay-inspired music of the past. The new pop Melayu sound was ‘cosmopolitan’ and internationalist. By ‘sounding’ elsewhere, pop Melayu looked in many directions at once and presented ways of imaging a future for Indonesian audiences that built the past into the present.

References:

Here, the musical development and socio-cultural meanings of pop Melayu (or Melayu pop)are discussed, a popular music genre created in Jakarta during the late-1960s that achieved commercial success in Indonesia during the 1970s. Pop Melayu blended Western-oriented pop and localized Melayu (also called Malay) music into a hybrid commercial form. Pop and Melayu had different symbolic associations with music, generation, social class, and ethnicity in Indonesia. Pop was marketed mainly to younger listeners who viewed it as ‘cool’ (gengsi) and progressive (maju). For this younger audience, ‘pop’ looked to the future. Conversely Melayu music had the connotation of ethnicity, tradition, and authenticity. Melayu music, as performed by Malay orchestras called orkes Melayu had a large audience base, but was not trendy. Under these conditions, what was the impetus for recording companies, producers, and musicians to create pop Melayu? What did the music mean to musicians, producers, and listeners within the context of culture and politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s? What were the implications of blending pop and Melayu for the future of Indonesian popular music?

During the politically and economically transformative period of the 1960s, pop Melayu grounded the present in the past. As Indonesia moved toward a system of Western-style capitalism, sustained industrialization and intensified commodification of culture, pop Melayu sonically transcoded images and memories of the past, albeit an imagined past, for Indonesian listeners. I borrow this concept of ‘transcoding’ from Ryan and Kellner’s analysis of film and social life: ‘Films transcode the discourses (the forms, figures, and representations) of social life into cinematic narratives. Rather than reflect a reality external to the film medium, films execute a transfer from one discursive field to another’ (Ryan and Kellner 1988:12). I will suggest that pop Melayu in the 1960s and 1970s mediated the contradictions and ambivalence of everyday life during a period of rapid social and cultural change. Musicians, recording companies, and producers were cultural mediators in this process.

In this chapter, I will describe the social and cultural conditions that made it possible to articulate ‘pop’ and ‘Melayu’ as a new genre. As a crossover genre, pop Melayu was a commercial effort to expand the market for popular music by bringing together or unifying diverse audiences. By 1975, a large number of prominent bands and singers had recorded pop Melayu albums.

Bands that recorded pop Melayu albums:

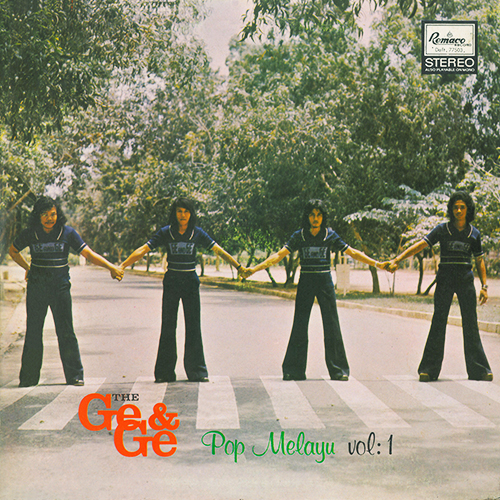

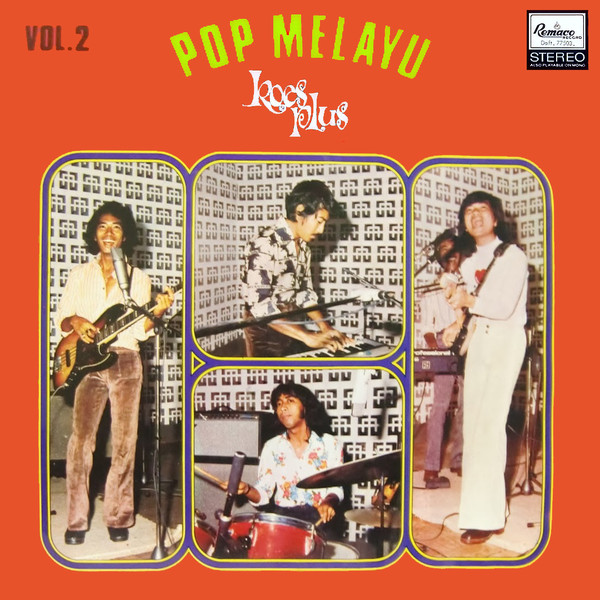

| Pop Melayu Vol. 1 (1974) Koes Plus Label: Remaco RLL-314 |

|

Album: Pop Melayu Vol. 1 Injit-Injit Semut (1974) The Mercys - Erwin Harahap Label: Remaco RLL-339 |

| Pop Meelayu Vol. 3 D'lloyd Label: Remaco RLL-343 |

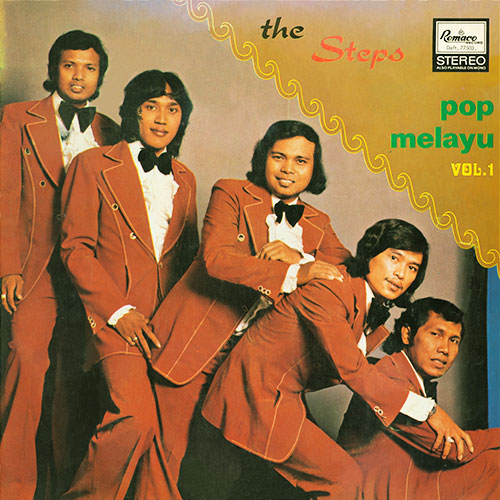

| Pop Melayu vol. 1 The Steps Label: Remaco RLL-433 |

Celebrated singers, Tetty Kadi, Emilia Contessa, Mus Mulyadi and Eddy Silitonga also recorded pop Melayu albums during the 1970s.

I situate pop Melayu within the social and cultural conditions of modernity in Indonesia in four thematic ways. First, its creative flowering coincided with the first decade of the New Order capitalist state in Indonesia. New private recording companies and private radio stations stimulated the development of new forms of music, new ways of advertising music, and an increase in sales of recordings. Second, as a ‘text’ about modernity, pop Melayu marked a transition between something old and something new. Change was articulated through sound, visual representation, and the discourse about pop Melayu in popular print media. Third, it was a form of modernity marked by ethnicity and specific to Indonesia. This “ethno-modernity” presented more than two alternatives: either the American-infused pop music of the future or the Malay-inspired music of the past. Fourth, it was music produced for a young generation and it helped set the course for the future of popular music. One article referred to pop Melayu musicians as the ‘generation of 1966’ (‘angkatan ‘66’); ‘Regrouping musikus Angkatan ‘66’ (1968:5).

Pop Melayu refers to a commercial genre of popular music and not simply any kind of popular music in the Malay (or Indonesian) language. My focus will be on the commercial genre of pop Melayu, and not other forms of Melayu popular music or popular music in the Indonesian language (bahasa Indonesia). Nor will this chapter address songs composed previous to the era of pop Melayu which might be considered precursors or progenitors of pop Melayu. Data are based on interviews with musicians, analysis of music and lyrics, depictions on record covers, and critical readings of popular print media from the period. I am grateful to Hank den Toom, Jr. for providing me with recordings from the period, and Ross Laird for recording data. I would also like to thank Shalini Ayyagari, Bart Barendregt, Henk Maier, Tony Day, and Philip Yampolsky for helpful comments during the writing of this essay. Particular emphasis is given to the work of Zakaria, an influential musician, composer, and arranger. The scope covered in this chapter encompasses the formation of pop Melayu around 1968 and it ends in 1975 when two things happened: (1) pop Melayu was established as a mainstream genre in the music industry; and (2) Rhoma Irama began taking contemporary Melayu music in a different direction, namely dangdut, which blended rock with Melayu. My interest here lies in the development and meaning of pop Melayu in its formative period.

Melayu

Central to my discussion of music in mid-1960s Jakarta is the notion of ‘Melayu’or Malayness. Melayu is a word of great slippage, and therein lies its productive force: it allows people to authorize all sorts of meanings (Andaya 2001). Defined in the colonial period as ‘stock,’ race, and ethnicity on the basis of biological appearances, Melayu implies a core set of ideas, values, beliefs, tastes, behaviours, and experiences that people share across geographical areas and history (Barnard and Maier 2004). The concept and naming of Melayu as culture and identity existed before colonialism but not as a way of organizing people according to physical markers of race and ethnicity. Some differentiation is necessary, and perhaps the terms ethnicity and race can be usefully applied. For example, Malays as an ethnic group (suku Melayu) resided around the Melaka Straits and Riau whereas Malays as a racialized group (rumpun Melayu) populate the modern nation-states of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, and (southern) Thailand in Southeast Asia. Yampolsky (1996:1) refers to the ethnic group as the ‘primary’ area of Melayu culture, and to, what I would call, the racialized group as the ‘secondary’ area of Melayu culture. For further on the construction of Melayu as a social category see Andaya 2001; Shamsul 2001; Reid 2004; Kahn 2006 and Milner 2008. However, Melayu never represented one uniform discourse, practice, or experience exclusive to all members of that group (Barnard and Maier 2004:ix). As a discursive category, Melayu has always been constructed, imagined, fluid, and hybrid. Melayu was an arena of constant reinvention. Notions of Melayu culture, language, and identity have always operated situationally and contextually (Andaya 2001).

What frames Malayness as a discursive category in popular music of the 1960s and 1970s in Indonesia? In contrast to the mistaken colonial idea of Malayness as cultural homogeneity and origins, I invoke Homi Bhabha’s notion of ‘ambivalence’ to understand the simultaneous attraction and aversion to Western colonial cultural forms in post-colonial Indonesia of the 1960s (Bhabha 1994). I aim to show how Malayness in popular music discourse of 1960s Indonesia represented: (1) the blending of Malay indigeneity and tradition (discursively constructed as ‘Melayu asli,’ or the ‘original’ or ‘authentic Melayu’) with Western forms, ideas, and practices; and (2) a ‘third space,’ where signs of the past could be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized, and read anew (Bhabha 1994:36; Rutherford 1990). In the politically transformative period of 1960s Indonesia, pop Melayu music formed links with discourses of indigeneity and tradition while simultaneously articulating with commercialization and modernity.

Melayu as a category of musical composition and performance did not represent a return to tradition in the face of modernity. Stylistic experimentation and compositional variety had long characterized Melayu popular music. The musical genres bangsawan, orkes harmonium, and orkes gambus of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries played mixed repertoires of Indian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, and Malay music. Orkes Melayu (Malay orchestras), which I will discuss further, continued this trend. Bangsawan (also called opera and stambul) troupes travelled from Malaya (Malaysia) to Java in the 1890s (Tan 1993:73; see also Cohen 2006; Takonai 1997 and 1998). Named after the harmonium, a small reed organ from Europe via India, orkes harmonium (or O.H.) included harmonium, violin, trumpet, gendang (small two-headed drum), rebana (frame drum), and sometimes tambourine. Radio logs indicate that orkes harmonium played a mixed repertoire of Malay, Arabic, Indian, and European music (Weintraub 2010:39-40). Gambus orchestras featured the gambus (long-necked plucked fretless lute) or ‘ud (pearshaped lute) and were accompanied by small double-headed drums (Ar. marwas, pl. marawis). Immigrants from the Hadhramaut region (Yemen) presumably brought the gambus and marwas with them to Indonesia (Capwell 1995:82–3). Even the term ‘orkes Melayu’ suggests mixing and contradiction: ‘orkes’ (from the Dutch ‘orkest’ or the English ‘orchestra,’ which denoted modernity) and ‘Melayu’ (signifying a cultural past). Melayu popular music was a ‘hybrid language’ (bahasa kacukan), the kind that always breaks the rules rather than follows ‘correct’ and standardized usage (Barnard and Maier 2004). Further, Melayu was a term of perspective: for example, ‘orkes Melayu’ had different musical properties and symbolic associations in Medan, Surabaya, and Jakarta during 1950 to 1965 (Weintraub 2010).

In the following section, I will trace the historical development of pop Melayu based on my interpretation of musical recordings, popular print media, and interviews with musicians and producers who were active during the period. I begin with the period of Sukarno’s Old Order (1949– 1965) because it informs an understanding of ‘pop’ for the purposes of this essay. I will focus on the formative period of pop Melayu recording, which occurred during 1968 to 1975 in Indonesia’s capital of Jakarta, the center for the production and consumption of pop Melayu.

The (Late) Old Order

The politically transformative decade of 1960s Indonesia is often characterized in terms of the fiercely anti-colonial and socialist-leaning Sukarno regime and the capitalistic and neoliberal economic policies of the Suharto regime. The transition from Sukarno’s Old Order (Orde Lama) to Suharto’s New Order (Orde Baru) took place mid-decade, after the military coup and subsequent killing of 500,000 to a million people beginning on October 1, 1965. Knowledge about cultural history of the period has been buried, particularly in Indonesia, due to the Suharto government’s effort to erase the PKI and the Left from the historical record. Recent scholarship has begun to investigate the cultural history of Indonesia 1950–65, particularly in terms of literature (Foulcher 1986; Day and Liem 2010; Lindsay and Liem 2012). However, studies of popular culture, especially popular music, remain unexplored (Lindsay 2012:18).

During the late 1950s, the anti-imperialist regime of Indonesia’s first president Sukarno denounced the allegedly harmful influence of American and European commercial culture (Frederick 1982; Hatch 1985; Sen and Hill 2000). The Committee for Action to Boycott Imperialist Films from the USA (PAPFIAS) boycotted American films in 1964 (Biran 2001:226). Sukarno viewed American and British music as symbolic and material markers of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. During a speech in 1959, Sukarno criticized the grating sound of American popular music, using the non-literal sounds ngak-ngik-ngok to characterize its noisy clatter (Setiyono 2001). As a result, popular music bands with Englishsounding names were compelled to switch to Indonesian ones to disarticulate the influence of American music. In a speech in 1965, Sukarno declared that ‘Beatle-ism’ was a mental disease and that he had ordered the police to cut the hair off anyone found listening to the Beatles (Farram 2007). Sukarno even imprisoned members of the American and British-influenced pop music band Koes Bersaudara (Koes Brothers) for 100 days in 1965 (Piper and Jabo 1987:11). As interesting and important as this case may be, I will not discuss Koes Bersaudara in this essay because I feel that their case has been covered amply in the literature on Indonesian popular music of the 1960s. Largely due to the banning and jailing of Koes Bersaudara, historians of the period have focused on Sukarno’s hostility to Western popular music (Lockard 1998; Sen and Hill 2000; Farram 2007).

Emphasizing the Old Order’s hostility to Western pop tends to obscure the diverse activities of musicians, producers, recording companies, and fans of popular music. Indeed, Sukarno attempted to ban Western popular music recordings from entering Indonesia in the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, despite Sukarno’s aversion to the sound of Western popular music, it still managed to cross geo-political borders. Although Western popular music was limited by government regulation on the national radio network RRI (Lindsay 1997:111), hundreds of illegal studentrun radio stations in Jakarta broadcast prohibited recordings of American popular music (Sen 2003:578). Recording companies continued to produce American- and British-sounding popular music, following trends established in the early 1950s. In addition, songs inspired by popular music of India, the Middle East, and Latin America energized the repertoire of the many orkes Melayu groups in urban Indonesia (Frederick 1982; Takonai 1997 and 1998; Weintraub 2010). Sukarno himself encouraged producers, composers, and musicians to mix regional songs with Western musical elements (Piper and Jabo 1987:10). Despite claims that the early 1960s was one of the most repressive periods in Indonesian music history, complete with national government censure of recording, radio, and public performances, the music of this period was productive in shaping ideas about modernity along the axes of social class, gender and ethnicity.

Orkes Melayu and pop Indonesia constituted distinct genre categories in terms of song lyrics/themes, language(s) used, instrumentation, performance practices and occasions, and audience. In the following section, I will elaborate on these genre categories and describe how pop Melayu combined elements of orkes Melayu and pop Indonesia.

Orkes Melayu

In 1960s Jakarta, orkes Melayu (O.M.) was an important genre term, but it actually describes several different kinds of ensembles, performance practices, and publics. At a very basic level, orkes Melayu was an ensemble of musical instruments (an ‘orkes’ or ‘orchestra’) used to accompany Malay-language songs. Songs were sung in a vocal style characterized by distinct kinds of ornaments (called gamak or cengkok) conventionally associated by musicians with the music of the Melayu ethnic group. Song forms included pantun verse structures as well as modern sectional forms (e.g., AABA). Pantun are made up of two couplets, generally structured into four lines with the rhyme scheme ABAB. The songs may have come from the geographic region considered the homeland of Melayu culture (in the southern Malay peninsula, Malacca, eastern Sumatra, and Riau), but they could also have been newly composed in a Melayu style in other parts of Indonesia including Jakarta. Either way, the repertoire, vocal style, and certain instruments in the ensemble signified a connection to Melayu ethnic identity or Malayness.

The instrumentation was not set. Recordings of orkes Melayu and photographs from the early 1960s reveal ensembles of Western instruments and two indigenous instruments, namely a small double-headed drum shaped like a ‘capsule’ (gendang kapsul) and bamboo flute (suling or seruling). The Western instruments could include accordion, violin, piano, vibraphone, acoustic guitar, string bass, woodwinds (flute, clarinet), brass (saxophone, trumpet), and percussion (maracas, in addition to the gendang kapsul). The historical and symbolic associations of the violin and accordion with Melayu music had been established earlier (Yampolsky 1996). Orkes Melayu bands could be heard on national radio programs, recordings, and in films. Although orkes Melayu has often been referred to as kampungan (regressive, backward, rural), it is hard to imagine these ensembles as such due to their centrality in mass media. See ‘Elvy Sukaesih’ (1972:18); ‘Peta Bumi Musik’ (1973:17); ‘Panen Dangdut’ 1975:48. A kampung refers to a neighbourhood that can be located in a village, town, or city. Kampungan connotes inferiority, lack of formal education, and a low position in a hierarchical ordering of social classes (Weintraub 2010; see also the next chapter by Emma Baulch).

Another kind of orkes Melayu was a pick-up group that performed in a variety of settings. Orkes Melayu was discursively coded as music of ‘ordinary people’ or ‘masses’ (rakyat). They were denigrated by elite youths as ‘kampungan’, country bumpkins, because they played an older kind of music. Orkes Melayu musicians and audiences themselves never thought of themselves as ‘kampungan,’ a term that expressed disdain. Orkes Melayu musicians in Jakarta viewed Melayu music with a certain amount of nostalgia, as expressed in the following quote by Zakaria in 1975:

Looking back for a moment, the birth of Melayu songs is like a step-child without a father. They were born on the side of the road, in ramshackle huts, next to railroad tracks, in food stalls, or in places where villagers hold celebrations, and even in lower class prostitution quarters. They danced to their heart’s content as they joked around to their dying day. They enjoyed these kinds of songs because they are easy to remember, the language is simple, and they are nice to listen to. Besides these psychological factors, the song texts give voice to suffering, love, sex, etc. Those songs, which are indeed sentimental at heart, are very appropriate to the emotional states of their listeners. See Zakaria (1975), ‘Sensasi Pop Melayu Ditahun 1975: “Begadang” yang jadi bintang’, Sonata 53, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

A comparison with pop music is instructive. Orkes Melayu bands had fewer resources than pop music bands. For example, they performed with only one microphone for the singer and one or two speakers for amplification. They were seen by elites as lagging behind pop music because they did not play electric instruments (guitar, bass, organ).

Their music was a hodgepodge and was viewed in a negative light by elites as impure or hybrid. Since the early 1950s, Indonesian composers had been copying Indian melodies from film songs and composing new lyrics in Indonesian. They played dance music with a wide range of Zakaria, pers. com., 2005). On the one hand, the repertoire for Orkes Melayu was old and conservative. On the other hand, the repertoire was vast and cosmopolitan and included Indian, Middle Eastern, Latin, and European songs. It did not look to the past or the present; it looked in many directions at once.

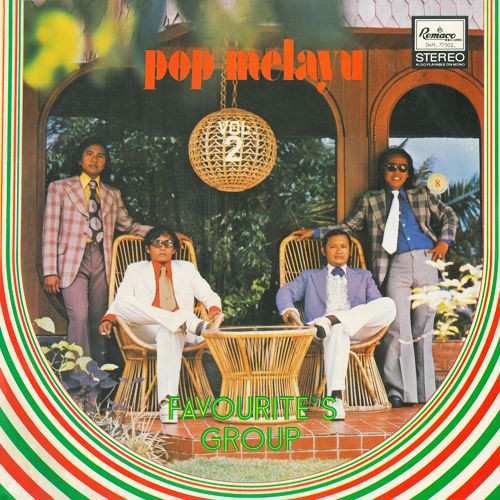

| Pop Melayu vol. 1 The Favourite's Label: Remaco RLL-247 |

| Pop Melayu Vol. 3 (1977) Fantastic (Fantastique) Group Label: Purnama PLL-1036 |

| Pop Melayu Vol. 1 Ge & Ge - Charles Hutagalung Label: Remaco RLL-629 |

| Pop Melayu vol. 2 The Favourite's Label: Remaco RLL-440 |

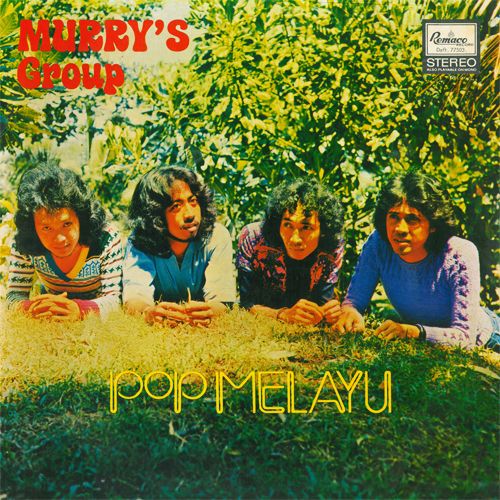

| Pop Melayu Murry's Group Label: Remaco RLL-841 |

| Pop Melayu Vol. 2 (1974) Koes Plus & Murry Label: Remaco RLL-347 |

Pop Indonesia

The nascent genre of pop Indonesia referred to music whose repertoire, song forms, arrangements, and instrumentation were rooted in American and British popular music. Also called band or band remaja (youth band), pop Indonesia was geared primarily to an emerging middle- and upperclass youth culture (‘the middle classes and up’). Pop Indonesia bands often played indoors in buildings (gedung), and earned the epithet gedongan (from gedungan) which implied class distinction and ‘progressive’ attitudes. Composer and musician Guruh Soekarnoputra, the son of Indonesia’s first president Sukarno, stated that the term gedongan and kampungan stemmed from identification with class distinction:

Pop Music in the past came to our country via ‘privileged youngsters’ whose parents had bought records from outside the country. They played these records at home and their friends heard them. Then they bought ‘band’ instruments and played them at their parties. Eventually the music got on the radio stations run by those youngsters. At that point youngsters outside [privileged residential districts] of Menteng and Kebayoran heard them. They began to think that this music was cool, and if someone was not familiar with that music, they would be considered a ‘country bumpkin’ (Soekarnoputra 1977:48). ‘Musik pop dahulunya masuk ke negeri kita lewat ‘anak-anak gedongan’ yang orangtuanya bisa membeli piringan hitam di luar negeri. Lalu diputar di rumah, dan kawan-kawannya mendengarkan. Kemudian mereka beli alat-alat band, bikin pesta dan main di sana. Akhirnya masuk ke pemancar-pemancar radio yang dibikin anak-anak muda. Mulailah anak-anak luar Menteng dan Kebayoran mengenalnya. Lantas timbul anggapan bahwa inilah musik keren, dan kalau tidak kenal sama musik demikian, bakal tetap jadi ‘orang kampung’.

Pop Indonesia was modeled on Euro-American mainstream popular music including pop, rock, and jazz. Pop Indonesia songs were accompanied almost exclusively by Western instruments (primarily guitar, bass, drums, and keyboard). Bands had a microphone for each person and multiple speakers. The language of pop Indonesia songs was Indonesian and English. It often incorporated vocal harmonies, in contrast to orkes Melayu, which generally consisted of a solo vocal part accompanied by instruments. Themes centred on romantic love. Musicians were often trained to read scores. They had financial backing that allowed them to purchase fine-quality instruments (Dunia Ellya Khadam 1972:36). Private radio played a large role in disseminating new forms of popular music during the New Order. During the Old Order, the national radio network RRI, as part of the Ministry of Information, had sole authority for broadcasting (Lindsay 1997:111). Amateur HAM radio operators existed and even had their own association; this type of operation was called amatir radio (which was different from radio amatir).

Private radio stations (radio amatir), suppressed during the Old Order, came back as part of the student movement of 1966 (Lindsay 1997:111). During the late 1960s, especially in Jakarta and Bandung, competing radio stations battled for airwave frequencies (Lindsay 1997:111). Private commercial radio stations flourished in the early New Order period (early 1970s), and they set themselves apart, respectively, by playing different kinds of music from each other.

In the late 1960s, production of popular music recordings increased. The Soeharto regime encouraged capital expansion in all sectors of the economy. Recording companies looked for ways to expand the market for products. Distinct markets existed for pop and Melayu in terms of recordings, concerts, and audiences, and both were successful. New fusion genres formed out of old ones. In the following section I will describe the efforts of the musician, composer, and bandleader Zakaria (1936–2010) who in the early 1960s began composing songs that blended pop with Melayu music.

‘Becoming Melayu’: The Work of Zakaria

Zakaria was born in 1936 in the area of Paseban in East Jakarta. He sang Melayu songs as a child growing up and cited the songs of the Malaysian singer and film star P. Ramlee as an important influence (pers. comm, 2005). Zakaria was self-taught as a musician (guitar) and was a talented singer. In 1956, he began singing with several orkes Melayu bands including Orkes Sri Murni (led by M. Masyhur) and Orkes Cobra (led by Achmad B.). He joined Said Effendi’s Orkes Melayu Irama Agung as a percussionist in 1957, and began composing shortly thereafter.

In 1962, he formed a group called Pancaran Muda (‘The Image of Youth,’ also called Orkes Melayu Pancaran Muda and Orkes Pancaran Muda). The band had a modern sound. With support from Jakarta’s popular entertainer Bing Slamet, Zakaria learned how to arrange music for an orchestra. He also worked on songs and new arrangements with pop and jazz pianist Syafei Glimboh, as well as violinist Idris Sardi. Zakaria’s songs com- bined elements of both genres. For example, in the song Luciana, the refrain (‘Luciana’) was composed in a pop style whereas the verse was Melayu (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). From the album Antosan featuring Lilis Surjani accompanied by Orkes Idris Sardi, Bali Record RLL-002, released in 1965–66.

In 1964, Zakaria produced the first commercially released songs by Elvy Sukaesih, a young 13-year-old singer who would later earn the moniker 'the queen of dangdut' (ratu dangdut). Elvy Sukaesih could sing both Melayu music and pop music and the songs on her first album were accompanied by a group made up of orkes Melayu musicians and pop (band) musicians. The session took place at the Remaco recording studio on December 19, 1964 and the record was released in January, 1965. The session included the following songs:

|

Album: Suswati (Label: Remaco RL-015) |

Zakaria’s Pancaran Muda did not emphasize the Indian-derived sound of orkes Melayu, which was discouraged in 1964 as the central government was trying to divert attention from Indian culture and refocus it on Indonesia. The Sukarno government, which had vigorously encouraged Indian film imports during the late 1950s and early 1960s, changed course by ceasing to allow imports during 1964–1966. As Indonesia became more isolated politically, songs with an Indian flavor (berbau India) were discouraged from being played on the radio (Barakuan 1964: 21; 'Orkes Melayu Chandralela’ 1964:21; ‘Dangdut, sebuah flashback’1983:15). The Indianderived songs of orkes Melayu, some of them direct copies from popular Indian films, were the targets of these efforts.

Zakaria mixed what he describes as ‘Melayu-India’ songs with Indonesian ones. In a description of his music taken from the album cover of Rohana released in 1967–68, Zakaria is quoted as follows: Liner notes written by Jul Chaidir on the back cover of the album Rohana featuring Elvy Sukaesih accompanied by Orkes Melaju Pantjaran Muda, directed by Zakaria (Remaco RL-050), c. 1967–68.

The song style that I present on my recordings is a mixture between music of Melayu-India and [pop] Indonesia itself. Since I do not copy a particular foreign song and then give it an Indonesian text, the songs will not sound like songs whose melodies and rhythms simply copy Indian songs. Tjorak lagu2 jang saja hidangkan dalam rekaman2 saja, ialah tjampuran antara lagu Melaju-India dan Indonesia sendiri. Djadi saja tidak menjeplak sesuatu lagu luar untuk kemudian diberikan teks Indonesia, oleh karena itu dalam lagu2 ini tidak akan terdengar lagu2 jang nada dan iramanja menjeplak lagu2 India thok.

There was a vacuum in popular music recording after the military coup and subsequent regime change from Sukarno’s ‘Old Order’ to Suharto’s ‘New Order’ in 1966–1967. From 1961 to 1963, Irama produced as many as 30,000 discs per month, but by the end of 1966 only pressed about 1000–2000 per month (and only sold about 500 per month) (MYK 1967). A similar gap is evident in Lokananta’s production of hiburan music (Yampolsky 1987:119–20). Deregulation of film imports, which began on 3 October 1966 (Said 1991:78), enabled greater access to foreign film music. Zakaria promoted singer Lilis Suryani as a competitor to singer Ellya Khadam, the top orkes Melayu singer of the era known for her Indianinspired songs Termenung (Daydreaming, c. 1960), Boneka dari India (A doll from India, 1962–63), and Kau pergi tanpa pesan (You left without a word, 1967); the latter was considered a ‘comeback’ for Melayu music à la India. From the album Pengertian featuring singer Ellya M. Harris accompanied by Orkes Melayu Chandralela, directed by Husein Bawafie (Remaco RLL-011), c. 1967.

Previously criticized by Sukarno as a symbol of imperialism and capitalism, American popular music was encouraged under the new president Suharto. Recordings of American-influenced pop Indonesia boomed in the late 1960s.

Zakaria was a savvy promoter of his band Pancaran Muda. Descriptions of Zakaria in popular print media depict him as a musical soldier for the nation. For example, ‘he had a face that looked like a soldier’; Tokoh Wadjar, 19 December 1965, as found in the private collection of Zakaria. another journalist referred to him as a ‘general’ of the band Pancaran Muda (bertindak sebagai panglima perangnya). His work was characterized as ‘revolutionary art’ (seni untuk revolusi) because it supported ‘the motherland that must be defended to the death’ (ibu pertiwi yang harus dipertahankan mati-matian). Mingguan Wadjar, 19 December 1965, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

In the late 1960s, Melayu-inflected songs accompanied by pop bands ascended in popularity. Successful songs in this vein included Boleh-boleh (It’s allowed) sung by Titik Sandhora and accompanied by Zaenal Combo (1968); Wajah menggoda (Seductive face) sung by Lilis Suryani (Remaco RLL-018, 1968),

and Tiada tjerita gembira (Not a happy tale) sung by Muchsin Alatas (Remaco RL-050, 1968).

After seeing positive sales figures from these and other songs, the Remaco recording company hired Zakaria as a producer, composer, arranger, and talent scout. Zakaria was instructed to create Melayu songs for a stable of pop singers:

Mr. Yanwar, the director of my section, told me that every singer who recorded at Remaco had to have a Melayu-type song on each record. It was a good opportunity for me [a composer of Melayu songs] that fans and pop singers liked Melayu songs. Subsequently, pop Indonesia bands like Bimbo, Koes Plus, Eka Jaya Combo, and 4 Nada recorded pop Melayu songs. (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005)

Zakaria taught pop singers Mus Mulyadi, Lilis Suryani, Wiwiek Abidin, and Titiek Puspa, among others, how to sing vocal ornaments typical of Melayu music (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). They were trained to sing in a more strident timbre than used in pop. Zakaria taught them to sing without too much vibrato, a hallmark of pop music. (Rh)Oma Irama, who had achieved success as a pop singer before becoming a star of contemporary Melayu music (dangdut), honed the Melayu vocal style by working with Orkes Melayu Chandralela bandleader Husein Bawafie who remarked: ‘He was often told not to sing with too much vibrato. Because dangdut is different from pop.’ (‘Ia sering diberitahu agar tidak terlalu banyak menggunakan vibra (getaran). Pasalnya, bernyanyi lagu dangdut berbeda dengan pop’ (Tamala 2000, no page numbers available). According to the composer, singer, and journalist Yessy Wenas, singers of Melayu songs had to be able to produce rich tonal variations, triplets, portamenti, punchy (staccato) tones, partial wailing, and shrill sounds. (Yessy Wenas, pers. comm., 2012). Penyanyi lagu Melayu harus punya teknik intonasi yang kaya variasi, not triol satu ketuk tiga nada, nada mengayun, menyentak, setengah meratap, melengking. He noted:

The singer Wiwiek Abidin felt stiff and encountered many problems when she began learning the ornaments of Melayu songs. But after a while she figured out how to sing in the style of Melayu songs in her own distinct way. Wiwiek commented that singing Melayu songs is easy to hear but difficult to follow because there are so many ornaments and there are almost no breaks [in vocal phrases]. She said that there are no definite rules, and only the composer of the song knows [the parameters of the composition]. (Lagu2 ‘dang dut’ mulai di senangi banyak orang, c. 1974). Penyanyi Wiwiek Abidin … merasa canggung dan menemui banyak kesulitan ketika baru mulai mengenal lekukan2 (intonasi) lagu2 melayu. Tapi lama kelamaan dia temukan juga gaya2 lagu melayu yang tersendiri ciri kasnya itu… Wiwiek memberikan komentar bahwa menyanyi lagu melayu adalah gampang di dengar tapi susah di ikuti, karena lekuk2an lagu melayu banyak sekali belok2nya dimana batas lekukan2 itu hampir tidak ada, katakanlah tidak ada patokan yang pasti, hanya pengarang lagunya saja yang tau’. See Wenas. J. (date unavailable, c. 1974), ‘Lagu2 “dang dut” mulai di senangi banyak orang’, as found in the private collection of Zakaria.

Yessy Wenas’s commentary noted that Suryani had figured out how to sing in a Melayu style (albeit in her own way). Despite not knowing the parameters of the style, she was able to recreate a style of singing that was convincingly Melayu-sounding. The composer Zakaria had his own definition that stressed the compromise or in-betweenness of pop Melayu. It was not ‘either/or’ but ‘both/and.”’ Zakaria defined pop Melayu simply as ‘When a pop singer sings a Melayu song in a pop vocal style accompanied by a pop music band’ (Zakaria, pers. comm., 2005). They may have inserted an ornament here and there, but the vocal style emphasized pop rather than Melayu.

Musical Style of Pop Melayu

In the following section I will examine two songs that merged pop and Melayu, focusing on texts and musical characteristics.

Djangan duduk di depan pintu (Don’t sit in front of the door), c. 1970, exemplifies the Melayu modernity of pop Melayu. The song is from the album entitled Kepantai Florida ([Let’s go] to the beach in Florida, Mutiara Records MLL 025). The cover of the album shows a photograph of Zakaria and female singer